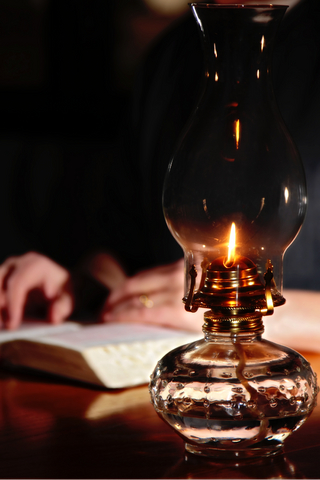

Stuff in books can help us pray. The monastics prayed through divine reading – in fact, a twelfth-century Carthusian monk by name of Guigo II worked out the four-step process that’s been in use ever since.

Stuff in books can help us pray. The monastics prayed through divine reading – in fact, a twelfth-century Carthusian monk by name of Guigo II worked out the four-step process that’s been in use ever since.

And what are those four steps? Reading, meditation, prayer and contemplation.

You’ll want to select a passage—a paragraph from a book, a short poem, or a few verses from Scripture. You can choose a favorite passage or one that you find challenging.

Before you start, take a few deep breaths. Now you’re ready to begin.

First, reading. Read your passage slowly several times, paying attention to the words, how they fit together, their rhythms, their meanings, their themes. If you’ve chosen a ‘secular’ poem or piece of prose, you may wish to rewrite it to turn it into a prayer. If you’ve chosen a theological or scriptural passage, rewrite it (if need be) to make it fit your theology. Or you can use the text as is—whatever works best for you.

Take this stanza from “Ode to the Table” by the Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda. The words in bold are Neruda’s originals; I added the italicized text to turn Neruda’s stanza into a prayer.

Oh God,

You made the world a table

“engulfed in honey and smoke,

smothered by apples and blood.

The table is already set,

and we know the truth

as soon as we are called:

whether we’re called to war or to dinner

we will have to choose sides,

have to know

how we’ll dress

to sit

at the long table,

whether we’ll wear the pants of hate

or the shirt of love, freshly laundered.

It’s time to decide,

they’re calling.”

Help us make the right choice, oh God.

Second, meditation. Which words or passages catch your attention? Sit quietly with them. Let them sit in your mind like stones in your hand, smooth if comforting, rough if challenging.

How would this work? If you used the Neruda example for your text-based prayer, you could reflect on the juxtaposition of honey/apple with smoke/blood. Or you could focus on the image of the world as a table—what would it mean to imagine the world as a place where you eat, where life is a meal—what would nourish you, what would make you ill, what would make you hunger for more? How about the idea that in times of war, we have to make a decision? If you had to choose sides, which would you choose? You could consider whether one side is always the side of hate and the other the side of love, as Neruda suggests.

Third, prayer. Respond to the meditation by praying, not intellectually, but by speaking (aloud or in your head) your own words directly to God.

Fourth, contemplation. Set all words aside if you can and enter into the space created by the word-prayers. This is a time of simple focus on God, a time of resting in God.

If you carry out the spiritual practice of divine reading at the same time every day, it will become a habit. An hour is ideal, or half-an-hour in the morning and another at night. This may sound like a lot but the mind often takes a while to settle into quiet receptiveness. Also, you’ll want to choose comfortable clothes and a comfortable place where you won’t be disturbed or distracted.

Four short steps. Try them. They just might work.

References: Pablo Neruda, “Ode to the Table,” in Odes to Common Things, trans. Ken Krabbenhoft, 19-21 (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company); Alister E. McGrath, Christian Spirituality: An Introduction (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 1999), 84-87. (For more suggestions on how to turn texts into prayers, see Post #9, Build-a-prayer-workshop.)

For Jews, Passover is supposed to be historically real.

For Jews, Passover is supposed to be historically real.

Think you’re number one?

Think you’re number one?

A quick glance at a few different faith traditions shows just how many ways there are to speak about the divine.

A quick glance at a few different faith traditions shows just how many ways there are to speak about the divine.

Your views on God (your theology) affect what you say when you pray.

Your views on God (your theology) affect what you say when you pray.