© Dreamstime Agency | Dreamstime Stock Photos

Ever wonder what an academic paper on theology looks like? Or wonder what this Naked Theologian does with her “spare” time when she’s not writing blog posts? Here’s a short paper that I presented in November 2012 to the Liberal Theologies Group of the American Academy of Religion (AAR), a yearly conference hosting more than 10,000 religion scholars. Should you choose to accept the mission of reading my paper, don’t worry about arcane technical language; there’s almost none (in order to be accessible to an AAR audience of specialists from a variety of disciplines). Also, the paper was intended for oral delivery and so avoids possible tongue-twisters. Enjoy!

Lived Religion and the ‘Agent-God’: Making a Case for the Personalist Theological Method of Gordon Kaufman

Gordon Kaufman’s constructive theology evolved significantly over the course of his decades-long career. However, since 1993, the year that he published In Face of Mystery, much of the scholarly engagement with his work has focused on this text and those that followed. This last phase of Kaufman’s theology with its impersonal concept of God as serendipitous-creativity has much to recommend it. However, I want to argue for renewed attention to the second, or personalist, phase of his theology.

In my view, there are three phases to Kaufman’s theology: first, Kaufman’s historicist phase; next, his personalist phase—so-called because he assumes that God-concepts will have person-like characteristics, and finally, his naturalist phase.

My case for taking a new look at the personalist phase of Kaufman’s theology and its associated theological method is based on a two-pronged argument:

First, during his personalist phase, Kaufman designed his theological method to facilitate the construction of God-concepts ranging from a sparse God to an Agent-God. This method is of special interest to theists who seek to construct, or more likely re-construct, a concept of God which is existentially meaningful, comforting in times of suffering, and which serves as an ultimate reference point. For the theists he has in mind, Kaufman writes, the word “God” “stands for” or “names” the “ultimate point of reference or orientation for all life, action, devotion, and reflection” (ETM, 17).

Second, the personalist phase of Kaufman’s theological method is well suited to the hybrid theologies that have become a fixture of the American religious landscape. His method, during this phase, is open to diverse religious and theological perspectives and to perspectives from science and secular humanism. But, for theists who incorporate a variety of religious symbols, rituals and texts from multiple traditions or from non-traditional sources to create individualistic theologies, Kaufman’s personalist phase provides checks to reduce the risk of producing Feuerbachian—or human-writ-large—God-constructs. And his method includes criteria to help theists identify the most humanizing symbols, rituals, and texts from among the plethora of possible options.

I now want to elaborate my first point—namely, that the personalist phase of Kaufman’s method, by offering a procedure for constructing an Agent-God, is helpful to theists who seek to construct, or more likely re-construct, a concept of God which is existentially meaningful, comforting in times of suffering, and an ultimate reference point, moral and otherwise.

In this phase of his work, Kaufman holds that the only God available to human beings is the concept of God that we imaginatively construct. He accepts Kant’s claim that it is impossible to have knowledge of God since God is not a “thing” like other “things.” Though God may exist, knowledge of God is beyond the capacity of our limited intellects. For this reason, Kaufman writes, “theology is (and always has been) essentially an activity of imaginative construction.”[1] Though imaginatively constructed, our concepts of God can play a central role in our lives. “Believing in God,” Kaufman argues, ”means practically to order all of life and experience in personalistic, purposive, moral terms, and to construe the world and man accordingly” (GP, 107, italics mine). For Kaufman, as for Kant, theology is above all a practical discipline (GP, 101).

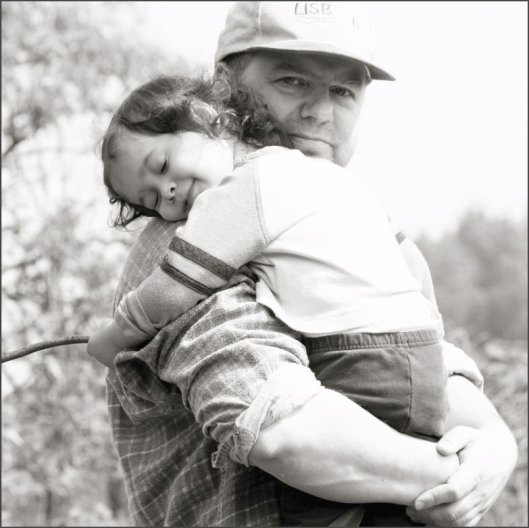

During the personalist phase of his theology, Kaufman anticipates that individuals constructing a concept of “God” are likely to incorporate terms, concepts, and metaphors drawn from their relationships, every day experiences, and familiar images (TI, 155). Indeed Kaufman recommends that “God” include anthropomorphic characteristics though he does not require them. However, Kaufman argues, unless we conceive of God as person-like, God can’t be existentially meaningful to us since “the human person is the only reality we know” for which our “concerns are of significance” (ETM, 65). Thus, Kaufman writes, “it is not surprising that metaphors such as ‘merciful father’ or ‘powerful savior’ were from very early on prominent in talk about God and that they remain among those which are more existentially meaningful to many” (ETM, 65). Indeed, these metaphors are also comforting to many in times of suffering. God as “merciful father” or “powerful savior” is, of course, an Agent-God.

The personalist phase of Kaufman’s method includes three mutually adjusting steps or moments as he calls them to signal that he does not intend them to be undertaken in any particular order and that they can be used recursively.

In broad strokes, Kaufman’s three moments for “methodologically sound theological work” are as follows (1995):

1. Construction of the concept, “world”

This moment entails a description of “reality” (for example, a phenomenological or scientific description).

2. Construction of the concept, “God”

The God-concept is required to include a “humanizing motif” for devotion, work, and practical orientation, as well as a relativizing motif to call into question our values, norms, and goals. I will have more to say about the humanizing and relativizing motifs when I discuss the second prong of my paper’s argument.

3. Adjustment of the concept, “world,” based on the relativizing and humanizing components of the concept, “God”

The concept of “world” is now to be understood as being “under God.” As a result, “world” may need to be adjusted to reflect the relativizing and humanizing components of the concept, “God.”

To recap the first prong of my argument, the personalist phase of Kaufman’s method is well suited to help theists who want to construct a person-like God who is existentially meaningful, comforting in times of suffering, and an ultimate point of orientation for their day-to-day decision-making.

Now, for my second reason for recommending renewed engagement with Kaufman’s middle, personalist phase—namely, that this phase of his method is well-suited to the hybrid, “lived” theological approach that has become a central feature of the American religious landscape.

Charles Taylor, in his 2002 Varieties of Religion Today, describes what he considers a new, contemporary age of “widespread ‘expressive’ individualism” (80). In the religious sphere, according to Taylor, expressive individualism means that (and these are Taylor’s words) “More and more people [are adopting] what would earlier have been seen as untenable positions, for example, they consider themselves Catholic while not accepting many crucial dogmas, or they combine Christianity with Buddhism, or they pray while not being certain they believe” (107). Though he traces this kind of expressiveness back to Europe’s Romantic period, what is new, he argues, is how it “seems to have become a mass phenomenon” (80).

More recently, Heidi Campbell, in her March 2012 Journal of the American Academy of Religion article, confirms Taylor’s assessment. Campbell reports that, in their autonomy, theists practice what she calls “lived religion.” By this, she means that theists pick a variety of religious symbols and narratives out of traditional structures and dogmas and then recombine them into new theologies. This mix of symbols and narratives often originate from multiple traditions including traditions previously considered non-religious. Like Taylor, Campbell finds that “pic-n-mix” (her expression) religiosity has become mainstream. She writes: “The process of mixing multiple sources of forms of spiritual self-expression…once done by individuals in private or on the fringes [is growing] more accessible and visible to the wider culture” (Campbell, 79).

Why is Kaufman’s personalist-phase method especially helpful for those who practice “pic-n-mix,” lived religion? Because, during this phase, his method is intentionally open to diverse religious and theological perspectives as well as to perspectives from science and secular humanism. Indeed, Kaufman assumes that encounters with other worldviews are important. These encounters, he believes, are bound to lead to discriminating and informed judgments about what is humanly significant. In his words:

The coming new age of a thoroughly interconnected and interdependent worldwide humanity must build upon the best insights and disciplines of all our long and varied human experience, as conserved for us in the many religious and cultural traditions alive and meaningful today. We must be open to all, in conversation with all (GMD, 40).

No doubt, picking and choosing from various models and images can lead to God-constructs that are formulated in terms of human needs and desires. As I mentioned earlier, Kaufman finds nothing strange about this. For God to be “God to us” and orient our lives, then our concept of God must share at least some of our human attributes and be capable of understanding our concerns in a significant way whether these are physical, moral, social, or cultural (ETM, 64).

While Kaufman’s personalist phase is open to anthropomorphic concepts of God, it is designed to combat anthropocentrism in two significant ways. Kaufman insists that any concept/image of God include what he calls 1) a humanizing motif and 2) a relativizing motif.

The humanizing motif of the God-construct helps transform us into” genuinely humane beings” and enables us to fulfill “our human potential” (TI, 32, 41). It is the humanizing motif that tends to introduce anthropomorphism into a concept of God. Powerful anthropomorphic images enable the God-construct to personify our highest and most important “ideals and values” (TI, 32, 41). Indeed, these images, Kaufman writes, can emphasize “the goodness of creation as a whole and specifically of human existence,…the importance of human communal existence and [of] just social institutions, a high valuation of morally responsible selfhood and such virtues as mercy, forgiveness, love, faithfulness, and the like…” (GDM, 94). In addition, the humanizing motif enables theists with a pic-n-mix religiosity to adjudicate between symbols, ideals, and artifacts and decide which to incorporate (or remove) from their hybrid God-constructs.

In contrast, the relativizing motif of the God-construct judges all of our achievements, according to “a very demanding norm,” to reign in our “tendencies toward anthropocentrism, hubris, and self-aggrandizement, our tendencies to make ourselves into gods instead of accepting our proper place within the creaturely order” (TI, 154-156). The relativizing motif “emphasizes God’s radical otherness, God’s mystery, God’s utter inaccessibility” (TI, 41). By virtue of its radical otherness, the God-construct provides us with “a center of orientation” outside of ourselves. As an ultimate reference point, the concept of God calls into question all of our projects, values, and goals. And because it calls into question everything finite, the relativizing motif of the God-construct even calls into question “every formulation or expression” of the concept of God itself (TI, 35, 87).

The humanizing and relativizing motifs are connected. If a God-concept is properly constructed, the two motifs operate as a powerful dialectic internal to its structure. The tension between them, Kaufman asserts, gives “the symbol much of its power and effectiveness as a focus for devotion and orientation in human life” (TI, 41). As long as “its highly dialectical character” is maintained and “its demand for continuous self-criticism” is honored, the God-construct cannot be “converted into an idol sustaining and supporting our own projects, but is apprehended as truly God,” forcing the self “into a posture of humbleness in its claims” (TI, 87).

I want to underscore the point that, during his personalist phase, Kaufman held that an anthropomorphic concept of God is not necessarily anthropo-centric. In fact, it is designed to fight against anthropocentrism.

It is true that he eventually decided that human beings are unable to resist 1) giving God-constructs ontological status and 2) reifying the anthropomorphic attributes of God-constructs. The only reliable way to deflate these impulses, he decided, was to make an impersonal God the proper object of devotion. Thus did Kaufman abandon his personalist phase. These considerations led him to the naturalist phase of his theology.

Yet, even in his naturalist phase, Kaufman recognized what I have argued in this paper—namely, that many theists continue to “opt for the more traditional agent-God” (IFM, 273). Despite the shortcomings that he came to associate with the Agent-God, Kaufman granted that this concept, “based on the model of the self-conscious and dynamic human agent, has been (and still is in many quarters) of great effectiveness in the ordering and orienting of human life” (IFM, 272). A world picture with an Agent-God at its core, he wrote in In Face of Mystery, continues “to function in important ways, not only among the traditionally pious but also in shaping ideals and goals in society at large” (IFM, 273).

Kaufman may not have fully anticipated contemporary “lived” religion or the degree to which theists today practice pic-n-mix religiosity, but the personalist phase of his theological method supports and even encourages exchanges between different religious, theological, and secular worldviews. This phase offers the possibility of constructing a wide range of God-concepts while also designed to defeat Feuerbachian God-concepts. The humanizing motif inspires theists to become more humane and to fulfill their highest potential; the relativizing motif calls the God-concept into question as well all of our projects, values, and norms.

Given these strengths, the personalist phase of Kaufman’s theological method deserves another look.

Endnote:

[1] Kaufman, “Theology as Imaginative Construction,” The Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol. I., No. 1, March 1982, p. 73.

References:

Campbell, Heidi. “Understanding the Relationship between Religion Online and Offline in a Networked Society.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 80:1 (2012): 84-93.

Choi, Yang Sun. “A Critical Study of Gordon D. Kaufman’s Theological Method.” Ph.D. diss., Drew University, 1995.

James, Thomas. In Face of Reality: The Constructive Theology of Gordon D. Kaufman. Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2011.

Kaufman, Gordon. “Theology as Imaginative Construction.” The Journal of the American Academy of Religion, I:1 (1982). Also GP, ETM, TI, IFM.

Nordgren, Kenneth. God as Problem and Possibility: A Critical Study of Gordon Kaufman’s Thought Toward a Spacious Theology. Uppsula, Sweden: Uppsula Universitet, 2003.

Taylor, Charles. Varieties of Religion Today: William James Revisited. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Gordon KAUFMAN’s book-length works organized by phase:

Phase I Historicist Phase (God-known-through-Christ-event)

RKF Relativism, Knowledge, and Faith (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1960)

CD Context of Decision (1961)

ST Systematic Theology: A Historicist Perspective (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968)

Phase II Personalist Phase (Imaginatively-constructed-agent-God)

GP God the Problem (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972).

ETM An Essay on Theological Method (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1975, 3rd ed, 1995)

NR Nonresistance and Responsibility and Other Mennonite Essays (Newton, KS: Faith and Life Press, 1979)

TI Theological Imagination: Constructing the Concept of God (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1981)

TNA Theology for a Nuclear Age (Philadelphia: Westminster John Knox Press, 1985)

Phase III Naturalist Phase (Steps-of-faith-process-God)

IFM In Face of Mystery: A Constructive Theology (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993)

GMD God—Mystery—Diversity: Christian Theology in a Pluralistic World (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996)

IBC In the beginning…Creativity (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004)

JC Jesus and Creativity (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004)